CS1: Lecture 1 – Hello, CS1

Dear students,

Welcome to CS 145: Programming for New Programmers or CS 148: Programming for Experienced Programmers!

It’s important to me that we have a comfortable working relationship. We are, after all, on the same team. You wanted to prepare yourself for a bright future, and so you asked me to give you some homework and exams to help you learn. Thank you for this opportunity! Because we’re on the same team, please call me Chris.

So that we can treat each other like humans, let’s get to know each other a bit. We’ll start with me. Here are some things about me:

- I just returned from a year of living in Australia and New Zealand. The transition back has been awkward, and I feel like my heart has been scattered across the globe.

- My wife and I have four children. I like you, but I love them and will not sacrifice them to you.

- I fell in love with the computer while trying to write a book in 5th grade.

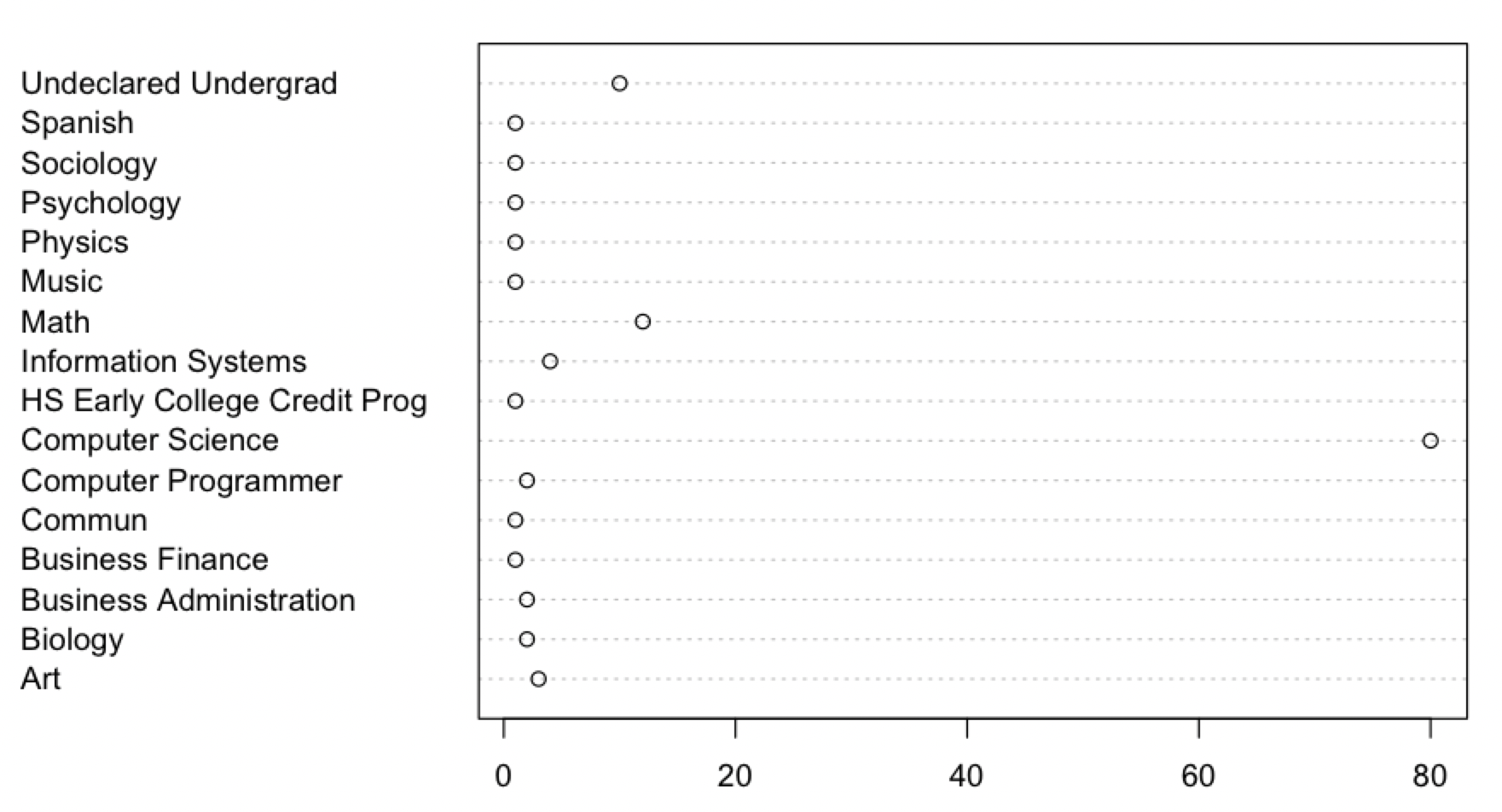

What about you? I know a little about you already just by you being in this course. This is the first course in the computer science major, but lots of other folks take it too. Check out the distribution of majors:

But I’d like to know a little bit more about you. Please answer the following questions on a quarter sheet of paper:

- What’s your name?

- Where are you from?

- What’s the last book you read that wasn’t assigned?

- What’s something about you that isn’t visible?

Now let’s discuss the content of this course.

Computer Science

What prompted you to take this class? Very few high schools teach such a course. Maybe you heard that computer scientists get paid well. Maybe your parents put you up to it. Maybe you saw that Googlers get free oil changes and haircuts. Maybe you are a gamer, and this class is your vehicle to that dream job of working at a stress-filled and divorce-provoking business that is the games industry. It’s quite likely that many of you have no idea what we will do in this class. And that’s okay.

Let’s hear how some folks have described the activities of computer science and specifically this class.

In 1961, a computer scientist named Alan Perlis presented this analogy:

calculus : rates :: computer science : process

In this class, we will program a process that turns the user’s input into the desired output. In a sense, we will become authors of information cookbooks. Our code will be like a recipe, describing to the computer how to combine and manipulate the ingredients that are our data.

Sometimes people don’t know whether to computer science fits better as an engineering discipline or as a science. Software engineer and computer graphics researcher Fred Brooks has this to say about the matter:

The scientist builds in order to study; the engineer studies in order to build.

In this class we will study and build. You can be either an engineer or a scientist; I don’t care.

Seymour Papert, an inventor of the Logo programming language, says this:

Way back in the mid-eighties a first grader gave me a nugget of language that helps. The Gardner Academy (an elementary school in an under-privileged neighborhood of San Jose, California) was one of the first schools to own enough computers for students to spend significant time with them every day. Their introduction, for all grades, was learning to program, in the computer language Logo, at an appropriate level. A teacher heard one child using these words to describe the computer work: “It’s fun. It’s hard. It’s Logo.” I have no doubt that this kid called the work fun because it was hard rather than in spite of being hard.

This class is about hard fun. You will make the computer do things. It will obey your every command. You will discover that the gap between you and the machine is wide. You will make a lot of mistakes. Thankfully, mistakes are free. The computer doesn’t mind trying again, though you might.

I personally summarize this class with one sentence: we will teach machines.

Hello, Java

We will spend the rest of our time today acquainting ourselves with the tools we will use for teaching machines: a programming language and a development environment. The language we will use is called Java and the development environment is called IntelliJ IDEA.

Let’s start with a little exercise I like to call Unscramble This. Using only our intuition, how can we reorder this code so that it conforms to the rules of Java?

public class Unscramble1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, CS1!");

}

}

We’ll paste this into IDEA and run it.

As we write code this semester, and you see lots of new ideas for the first time, you will question things. Why is there that class thing? Why is there an args? Why is there a semi-colon there? Most of your questions will get answered in time, but one unsatisfactory answer that we can give right away is that technology is an oligarchy, sometimes even a monarchy. The inventors of a thing make decisions to which its users are subject. Accordingly, let’s establish a few decrees that have been made in the Kingdom of Code. In just these five lines of code, we can see three big ones.

Decree 1: There is data and there are instructions.

The world has atoms and forces, just as programs have data and instructions. The data here is "Hello, CS1!". The instruction is println.

Decree 2: Code can be ours, or it can be someone else’s.

We didn’t write the code for println. Someone else did—in the 1990s. This is one of the few things that has lasted from that decade. Sometimes I will call other people’s code OPC. Usually this term is said with disdain, much as you’d say OPS when talking about other people’s shoes or OPH for other people’s hair.

Decree 3: Data can be mailed from our code to someone else’s code.

Some, but not all, parentheses are a mailbox. If we put our data between them, it will get shuttled off to the other code that needs it to do its job. println for instance has no idea what to print without us telling it.

Let’s have a try at another Unscramble This:

public class Unscramble2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int a = 956;

int b = 213;

int c = a / b;System.out.println(c);}

}

This program has some new forms in it, which lead us to some new decrees.

Decree 4: Data can be named.

We have three pieces of data here: 956, 213, and something else. We’ve named all three using the names a, b, and c. Naming is accomplished through a declaration. Declarations must appear before the names are referenced elsewhere.

But the names aren’t good. Our friends in mathematics are often stuck with single letter names. To get more, they stick on hats and bars and apostrophes. In computer science, we can have longer and more meaningful names. This program is much more interesting with these names:

public class Unscramble2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int nDaysInOffice = 956;

int nGolfOutings = 213;

int golfRate = a / b;

System.out.println(golfRate);

}

}

Decree 5: Data has a type.

The data we saw in the first program was text. Now we have whole numbers. All of our data will have a certain shape or type. We see the type explicitly when we name data using a declaration, which has one of these two forms:

type name; type name = data;

Decree 6: Data can craft new data.

Just as you combine five gunpowder and four sand in Minecraft to craft TNT, you can craft new data. a / b crafts the quotient of a divided by b. The / is called an operator. But we must be careful. The behavior of operators depends on the types of the data they are combining. In this case, a is an int and b is an int. So / yields an int. There are ways to make it produce a number with a fraction, but that’s a story for another day.

Let’s unscramble another:

public class Unscramble3 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner in = new Scanner(System.in);

int x = in.nextInt();int y = in.nextInt();int result = x + y + x + y;System.out.println(result);}

}

In this code we see a new type of data. The data is named in and is of type Scanner. Its declaration is more complex than our other declarations, but that’s a decree for another day.

We also have names x and y, but the data comes from someone else’s code—from in. That leads us to our next decree.

Decree 7: Other code can mail data back to our code.

The code for nextInt is effectively going out to the keyboard and collecting our keystrokes. It does all the hard work and hands the result back to us. We must catch the result and do something with it, like name it in this case.

Not all code has a result to send back. For example, println didn’t send anything back.

Let’s unscramble one more:

public class Unscramble4 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner in = new Scanner(System.in);

String a = in.nextLine();String b = in.nextLine();String c = a + " \u2764\ufe0fs " + b;

System.out.println(c);}

}

Here we give a name to the text type that we saw earlier: String. We see that the Scanner type can mail us back a String. Also, we can craft a String with a String to produce a new String.

TODO

Often when we meet for lecture, I will ask you to do some reading or activities and jot down some observations or reactions on a quarter sheet of paper to be turned in at the beginning of the next class. Since I have a large pile of these to read and sort through, I ask that you form this quarter sheet by dividing a piece of paper in half exactly twice, once vertically and once horizontally.

Consider these quarter sheets as personal and relevant notes to me. Without them, I can only guess what’s going on inside your head.

I will have a box in front of the room for you to turn these quarter sheets in. That box will be whisked away soon after class starts. To receive participation credit, you must have your sheet in the box before it disappears. Don’t worry too much if you miss some. There will be occasional extra credit opportunities to regain participation points.

Here’s your TODO list of things to complete before next class:

- Read the syllabus.

- Complete this short background survey. Completing this is worth one participation point.

- If you have your own computer, do the following:

- Install the OpenJDK Java Development Kit. Install version 11 for maximum compatibility with the lab computers. In the past, we’ve often used Oracle’s JDK, but the license for the Oracle JDK is no longer free.

- Install IntelliJ IDEA 2019.2.

- Log in to Piazza. I added everyone who was registered last Friday. Let me know if you did not receive an invitation email.

- Read chapter 1 through section 1.3 in your textbook.

- Write down 2-3 questions or observations about the class or from your reading on a quarter sheet to be turned in at the very beginning of the next lecture. This is worth one participation.

See you next class!

P.S. It’s time for a haiku!

“Hello, world!” it said

“What’s your mother’s maiden name?”

I started early

P.P.S.

When we write code together in class, I will share it here. I recommend that you leave your laptops home. I think you’ll get more out of lecture by participating than trying to clone our work up front.

Unscramble1.java

package lecture0904.cs145;

public class Unscramble1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, CS1!");

}

}

Unscramble2.java

package lecture0904.cs145;

public class Unscramble2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int nDaysInOffice = 956;

int nGolfOutings = 213;

int golfRate = nDaysInOffice / nGolfOutings;

System.out.println(golfRate);

}

}

Unscramble1.java

package lecture0904.cs148;

public class Unscramble1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, CS 148!");

}

}

Unscramble2.java

package lecture0904.cs148;

public class Unscramble2 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int nDaysInOffice = 956;

int nGolfOutings = 213;

int golfRate = nDaysInOffice / nGolfOutings;

System.out.println(golfRate);

}

}

Unscramble3.java

package lecture0904.cs148;

import java.util.Scanner;

public class Unscramble3 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Scanner in = new Scanner(System.in);

int x = in.nextInt();

int y = in.nextInt();

int result = x + y + x + y;

System.out.println(result);

}

}