Homework 5 – Plaid Scientist – due December 1

Your objective in this homework is to learn how to organize and process data using arrays. You will do this in the context of writing a program that generates plaid patterns.

Arrays have two features that are indispensible when building software: they help us manage large sequences of data by collecting the data into a single container, and they let us reach into the data with integer indices—which means we can write all sorts of algorithms that look up or access data indirectly.

This assignment is more involved and less easy to test in small chunks than your previous assignments. Plan accordingly.

Before we dig into the specification, let’s talk about plaid and the file formats you will be using.

Plaid

Plaid patterns are generated by weaving together yarns of different colors in algorithmic patterns. One can use a rectangular frame or loom to generate these patterns. First, yarn is stretched from the top of the loom to the bottom in a series of columns or warps. Then horizontal strands of yarn are weaved through the warps. Because these horizontal strands are the active agents of the weaving, they are called wefts.

Twill

The weaver has choices about how to string the horizontal wefts through the vertical warps. One could go over one warp, under the next, over the next, under the next, and so on. This pattern is called a 1/1 twill. If the weaver goes over two warps, under one warp, over two warps, under one warp, and so on, a 2/1 twill pattern is produced. A 3/2 twill pattern goes over 3 warps, under 2, over 3, under 2, and so on.

Color

The yarns themselves are dyed in repeating patterns. For example, a yarn might be dyed cornflower blue for 2 inches and pumpkin for 1 inch, with this pattern repeated along the whole length of the yarn.

The combination of the geometric alternation of the twill and the alternation of colors of the warps and wefts produces the comforting plaid patterns that we find in our flannel shirts, tablecloths, and other fabrics.

Plaid Pattern Specification

In this homework, we describe plaid patterns in a plain text file that has a form like the following:

hmirror true vmirror false twill 3 1 palette salmon 240 142 125 marzipan 240 200 125 endpalette yarn salmon 2 marzipan 4 endyarn

There are five possible commands: hmirror, vmirror, twill, palette, and yarn. They may appear in any order. There may be multiple palette and yarn sections—but if you follow the pseudocode suggested later, you don’t need to do anything special to support this. We will consider how these commands are interpreted in the following sections.

Yarn

In the example plaid pattern shown above, we see that the yarn alternates between 2 units of salmon and 4 units of marzipan. The RGB values of these colors are defined in the palette section. The base yarn pattern looks like this:

We use this base pattern to form the colorings of the warps and wefts.

Warp

The vmirror property is false, so we use the base yarn pattern directly to form the vertical warp pattern:

When strung on the loom, the warp pattern will repeat to span the loom’s height:

If we were to string 12 of these warps on a loom, we’d see the following color pattern:

…

This is not how the final fabric appears. We still need to string the wefts through.

Weft

The weft is different because hmirror is true. Instead of repeating the base yarn pattern directly, we mirror it first. The base is 2 salmon and 4 marzipan, and therefore the mirrored pattern is 2 salmon, 4 marzipan, 4 marzipan, and 2 salmon:

When repeated along the width of the loom, we see this for the wefts:

If we laid out a number of wefts as we did with the warps, we might suppose we’d see a pattern like this:

To add some visual variety, however, weavers shift the pattern one step after each row, like so:

Weaving Algorithm

We now know what a fabric of all warps would look like, and we know what a fabric of all wefts would look like. But a weave is a selective combination of the warps and the wefts. The twill pattern tells us which of the two will be visible. If the twill is 2/1, we see weft-weft-warp, weft-weft-warp, and so on. If the twill is 3/1, we see weft-weft-weft-warp, weft-weft-weft-warp, and so on.

Suppose we weave the plaid patterns in an image instead of a loom, stringing the warps along its columns and the wefts along its rows. At each pixel, we must decide whether we use the color from the warp or the weft. Considering all the information above regarding the twill, warps, wefts, and shifting, we formulate this algorithm:

period = over count + under count

for each row r

twill index = 0 for row 0, 1 for row 1, etc, with wrapping

for each column c

if twill index says we're in weft zone

choose color from weft according to c, with wrapping

else

choose color from warp according to r, with wrapping

set pixel to chosen color

advance twill index by 1, with wrapping

Though not shown in this pseudocode, the twill index must always wrap back around to 0 when it reaches the period or beyond.

PPM

To visualize the color data that we generate by our weaving algorithm, we have to write it out in a format that image editors can read. JPEG and PNG are popular formats, but they use mathematics beyond the scope of this course to shrink down the file size. We will instead use a very readable format called Portable Pixmap (PPM).

Humans can open a PPM file in a text editor and understand it with some labor. Consider this PPM, for example:

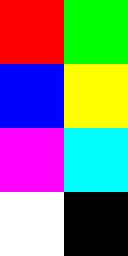

P3 2 4 255 255 0 0 0 255 0 0 0 255 255 255 0 255 0 255 0 255 255 255 255 255 0 0 0

The first line is P3. Many file formats specify a magic number, a special sequence of bytes that tells applications what kind of file it is. P3 is the magic number for the PPM format. The second line (2 4) is the image’s width and height. The third line (255) is the maximum intensity found in any color. A color whose red, green, and blue components are this number will display as white. For our purposes, assume this number is always 255. The next lines are the individual pixel triplets, row by row. The first pixel in this example is red, and the second is green. Then we have blue and yellow. Then magenta and cyan. And finally white and black. The first pixel in the file is shown at the top-left of the image.

Paste the text into a file and view it with an image editor like The GIMP. Not all editors can read PPM. You should see an image that looks like this:

Tweak color values in the text file and see what happens. Make sure you understand the file structure before moving on.

Requirements

Complete the classes described below. Place all classes in package hw5. Make all methods static.

Main

Write class Main with a main method, which you are encouraged to use to test your code. Nothing in particular is required of it, but it must exist.

ImageUtilities

Write class ImageUtilities with the following methods:

- Method

writePPMthat exports a 2DColorarray to an image file in the Portable Pixmap (PPM) format. It accepts two parameters in the following order:Assume the array is organized in row major order, meaning that the first index is the row, and the second is the column. This method writes the array to the file according the PPM format described above. Use platform-independent line breaks (- a

Fileto which to write - a 2D

Colorarray of pixels

println, orprintfwith%n). Use aPrintWriterto handle the output; it has the same methods asSystem.out. - a

- Method

pixelsToImagethat converts a 2DColorarray to aBufferedImage. It accepts a 2DColorarray of pixels as its sole parameter. Assume the array is organized in row major order, has at least one row of pixels, and has rows that are of identical length. It returns aBufferedImageof typeTYPE_INT_RGB. This method is useful for testing. You could, for example, call this method inMain, and useImageIO.writeto save the image in a more standard format than PPM.

PlaidUtilities

Write class PlaidUtilities with the following methods:

- Method

extendSequencethat appends a color to a list a certain number of times. It accepts three parameters in the following order:For example, suppose- A list of colors of type

ArrayList<Color> - A color to add of type

Color - A run-length, or the number of times to append the color, of type

int

listcontainsColor.REDandColor.GREEN. ThenextendSequence(list, Color.BLUE, 2)changes the list so that it has elements [Color.RED,Color.GREEN,Color.BLUE,Color.BLUE]. - A list of colors of type

- Method

mirrorSequencethat appends a reversed version of a list to itself. It accepts as its sole parameter a list of colors of typeArrayList<Color>. SupposelistcontainsColor.REDandColor.GREEN. ThenmirrorSequence(list)changes the list so that it has elements [Color.RED,Color.GREEN,Color.GREEN,Color.RED]. - Method

parsePalettethat parses the palette section of a plaid pattern, an example of which we saw earlier in the Plaid Pattern Specification. It accepts three parameters in the following order:The two lists are associated with each other. That is, name- a

Scannerthat’s poised to read the first color entry - a list of color names of type

ArrayList<String> - a list of colors of type

ArrayList<Color>

iis the name given to colori. This method reads colors until it encountersendpalette. Names are appended to the names list, and colors are appended to the colors list—maintaining their association. For example, suppose the text about to be read is this:cornflower 100 149 237 teal 0 128 128 endpalette

Suppose thatnamescurrently holds ["background"] andcolorsholds [Color.BLACK]. After a call toparsePalette(in, names, colors),nameswill hold ["background","cornflower","teal"], andcolorswill hold [Color.BLACK,new Color(100, 149, 237),new Color(0, 128, 128)].Spreading data that is linked together, like these colors and their names, across multiple arrays is not necessarily the best design. (These linked arrays are sometimes called parallel arrays.) We will see a better way of keeping linked data together when we start creating our own objects.

- a

- Method

parseYarnthat parses the yarn section of a plaid pattern, an example of which we saw earlier in the Plaid Pattern Specification. It accepts three parameters in the following order:The two lists are associated with each other. That is, name- a

Scannerthat’s poised to read the first color entry - a list of color names of type

ArrayList<String> - a list of run-lengths of type

ArrayList<Integer>

iis associated with lengthi. This method reads yarn colors until it encountersendyarn. Names are appended to the names list, and lengths are appended to the lengths list—maintaining their association. For example, suppose the text about to be read is this:cornflower 5 teal 3 endyarn

Suppose thatnamescurrently holds ["border"] andlengthsholds [2]. After a call toparseYarn(in, names, lengths),nameswill hold ["border","cornflower","teal"], andlengthswill hold [2, 5, 3]. - a

- Method

colorByNamethat looks up a named color from a set of colors stored in parallel lists. It accepts three parameters in the following order:The two lists form a “directory”. Name- a list of names of type

ArrayList<String> - a list of colors of type

ArrayList<Color> - a name of type

String

iis the name used to identify colori. This method determines theColorassociated with the given name by iterating through the names list until it finds the given name and returning the associatedColor. If the name cannot be found in the directory, it returnsnull. - a list of names of type

- Method

generateSequencethat expands a list of colors names and their run-lengths into a single flat list of colors. It accepts five parameters in the following order:This method returns a new- a list of color names in the palette, of type

ArrayList<String> - a list of colors in the palette, of type

ArrayList<Color> - a list of color names in the yarn, of type

ArrayList<String> - a list of run-lengths in the yarn, of type

ArrayList<Integer> - a

booleanthat is true if the sequence should be mirrored

ArrayListofColorthat is produced by traversing the yarn colors, appending each named color to the returned list. The number of times each color is appended is determined by the color’s run-length. For example, suppose we’ve got the following variables:ThenpaletteNameswith elements ["light","dark"]paletteColorswith elements [Color.LIGHT_GRAY,COLOR.DARK_GRAY]yarnNameswith elements ["dark","light"]yarnRunLengthswith elements [2, 1]

generateSequence(paletteNames, paletteColors, yarnNames, yarnRunLengths, false)→ [Color.DARK_GRAY,Color.DARK_GRAY,Color.LIGHT_GRAY]. If the sequence is mirrored, then we have [Color.DARK_GRAY,Color.DARK_GRAY,Color.LIGHT_GRAY,Color.LIGHT_GRAY,Color.DARK_GRAY,Color.DARK_GRAY]. Call upon other methods you’ve written to do most of the grunt work. For reference, your instructor’s non-magical solution is 9 lines of code. - a list of color names in the palette, of type

- Method

weavethat produces a plaid pattern of a certain resolution. It accepts six parameters in the following order:It returns a 2D array of- an image width of type

int - an image height of type

int - a warp pattern of type

ArrayList<Color> - a weft pattern of type

ArrayList<Color> - a twill’s over count of type

int - a twill’s under count of type

int

Color, which is filled according to the Weaving Algorithm described in pseudocode above. - an image width of type

- Method

generatePlaidthat reads in a plaid pattern and returns the plaid image as a 2DColorarray. It accepts three parameters in the following order:This method should follow this general pseudocode:- the

Filecontaining the plaid pattern - an image width of type

int - an image height of type

int

set up needed variables # do parsing while there's a command to be read read command if command is this respond to this else if command is that respond to that ... use variables to generate arrayThis method consumes a number of lines of code because of the loop, but most of its meat is accomplished by calling methods defined above. - the

Extra

For an extra credit participation point, identify some plaid in your life and recreate it using your program. Share a photo of the original plaid, your plaid pattern, and a resulting PNG image on Piazza under folder ec5 by the due date. The submission garnering the most votes will be honored in some way.

Submission

To check your work and submit it for grading:

- Run the SpecChecker by selecting

hw5 SpecCheckerfrom the run configurations dropdown in IntelliJ IDEA and clicking the run button. - Fix problems until all tests pass.

- Commit and push your work to your repository.

- Verify on GitLab that your submission uploaded successfully.

A passing SpecChecker does not guarantee you credit. Your grade is conditioned on a few things:

- You must meet the requirements described above. The SpecChecker checks some of them, but not all.

- You must not plagiarize. Write your own code. Talk about code with your classmates. Ask questions of your instructor or TA. Do not look at others’ code. Do not ask questions specific to your homework anywhere online but Piazza. Your instructor employs a vast repertoire of tools to sniff out academic dishonesty, including: drones, CS 1 moles, and a piece of software called MOSS that rigorously compares your code to every other submission. You don’t want to live in a world serviced by those who achieved their credentials by questionable means. For your future self, career, and family, do your own work.

- Your code must be submitted correctly and on time. Machine and project issues are common—anticipate them. Commit early and often to Git. Extensions will not be granted. If you need more time to make things work, start earlier.